One of the perks of attending a TBEX (Travel Blogger Exchange) conference are the pre and post conference tours and media trips offered to conference attendees. This was how I found myself face to face with a significant episode in the history of the Philippines, as well as a glimpse of the past through the eyes of my own family. My signing up for the pre-conference Ruins of World War II: Corregidor Island Tour was more for the promise of ghosts rather than history.

But my own bloodline has much in common with the Filipinas, and the Corregidor Island tour included three glaring words which caught my eye and struck a familiar chord. World War Two. I’ve had an odd fascination with the movements of Japanese forces, in Southeast Asia since I first heard stories told in Malaysia.

This may make you wonder what that has to do with my own past, but I’ll get to that later.

Standing in a musty cave on Langkawi’s Tuba Island I tried to imagine if I could live there for months. According to a tour guide, at the time, Tuba Island locals crammed themselves into caves as the Japanese arrived in the archipelago. A stranger I bumped into at the Field of Burnt Rice mentioned ‘comfort women’ to me and confided that one Langkawi local was taken by the Japanese. I knew nothing about comfort women at the time or even the extent of that particular horror. Until recently, when I purchased a book by the same name.

On a trip to Kota Bharu, Kelantan, I visited the war museum and viewed the pristine relics of a once-upon-a-time. There were old photographs of Japanese soldiers riding simple bicycles into a quiet Malaysian town as if to innocently mask their true aggressive desires. Innocent young men in wolf’s clothing. I later saw a similar museum in Songkhla, Thailand. Another entry port for the Japanese forces. A door which was held open by Thailand who offered them little resistance or quarrel.

But the Malaysian’s were not easily fooled and word had already spread far and wide. Girls across Malaysia had their hair shorn to look like boys or instructed to look as dirty and unattractive as possible. Including rubbing dirt and mud on their faces. A hotelier in the Perhentian Islands showed me her father’s diary from the time. He had written of his own mother hiding his sister when Japanese soldiers were spotted.

An elderly 82-year old woman on a flight from Langkawi to Kuala Lumpur, peeked at me from under her Hijab. When asked where her parents were from, she whispered, “I’m Chinese. I was told that my parents were killed by Japanese soldiers. I was adopted by a Malay family who raised me as their own.”

Words and stories from strangers I have met over the past few years.

I visited the grave sites at the Ambon Memorial Cemetery in Ambon, Maluku, Indonesia. Yes, the Japanese had been there too. The promise of a new happier all for one and one for all Asia sounded very attractive to the Indonesian’s, who were already accustomed to dealing with the ugly side of colonialist intruders. The Indonesian’s took a gamble and lost. And sadly the resulting Battle of Ambon was a slaughterhouse.

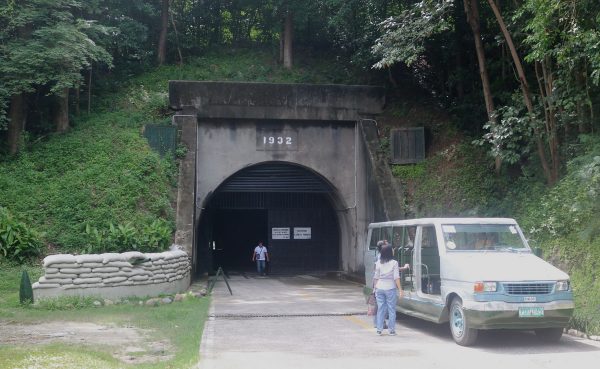

So as I took the cheerful ferry from Manila for the sightseeing tour, my expectations were not more than the possibility of seeing a few old bunkers, a small museum or maybe a relic or two. And indeed I did. We were escorted classic tourist style in an open-air tram. As we snaked our way around the island our enthusiastic guide pointed out various points of interest and peppered the air with multiple historic facts.

I did my best to soak it all in, but what really struck me was the uniqueness of the island, in that beyond an extremely well maintained landscape, there were few signs of restructuring or impending development. Sans the one, that I know of, small hotel and restaurant.

In Corregidor Island there also wasn’t the true ugliness of what the Japanese forces had done to the Philippines or any other places they had deemed worthy of their attention. Corregidor Island is a living museum. A frozen statement of the diligent efforts of American and Philippine armed forces who fought to stop the destructive machine of the Imperial Japanese forces.

Frozen in time are the ghostly shells of bombed buildings embraced in the tangled loving embrace of tropical greenery. Pristine grassy hills with the echoes of leisurely ball games played and the groans of dying men. The whispers of the past passing through ancient trees and hollow buildings. A beautiful memorial to the deceased soldiers who gave their lives, and the reminder to the survivors that it was indeed real, and not a bad dream. A place where soldiers could return to pay their respects and make peace with the enemy.

Corregidor Island’s own history started long before World War II, but it pales in comparison to its legacy.

The Spanish arrived in the 1500s. The Dutch arrived in the 1600s. The Americans arrived in the early 1900s. The bloodlines of future generations emerging along the way and scattered across the region. Including nearby Guam. As I stood in front of a shiny plaque I saw my own reflection against the names of all the locations Corregidor soldiers had helped by fighting so bravely, I saw Agana, Guam listed, and I remembered my own bloodline.

I connected historic dots and whispered secrets from my own grandmother late at night. She despised the Japanese and I never really understood why. My own grandmother was born and raised in Guam. A land I only know as having much Spanish influences akin to the Philippines. Surnames, religion, foods and many traditions.

My grandmother’s own mother Dolores Flores Torres was a full blooded Chamorro who married an American expatriate named Peter Nelson. He worked for the Guam Department of Agriculture in the early 1900s. Her brother of the same name witnessed the Japanese take over of their own family home on the shores of Agana. Thankfully my own grandmother had already been whisked away to America by her American soldier husband. Where my bedtime stories were stories of her life.

I was lucky to have my grandmother, as many future grandmothers and grandfathers never had a chance to whisper secrets to their future grandchildren. World War II took their chances away. An atonement of a gruesome historic era now whispered through hollow buildings and bunkers of Corregidor Island.

My Ruins of World War II: Corregidor Island Tour was generously sponsored by Sun Cruises , the Tourism Promotions Board Philippines and Intas Destinations Management.

For more information on tours of Corregidor Island:

Sun Cruises: [email protected]

Tourism Promotions Board Philippines: [email protected]

Intas Destinations Management: [email protected]

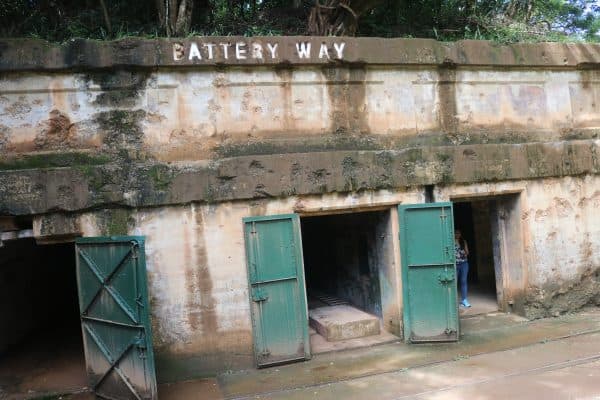

I first went to Corregidor in 2007. I had a good knowledge of its history and as The Rock. I believe that if ghosts are real, then they’re on Corregidor. I’ve been back to The Rock a couple more time since my first visit. I stayed overnight both times because my first visit wasn’t enough for me. History is everywhere on the island. I lover being alone in Geary or walking into the darkness of Way’s magazines hoping to spot an artifact which I have found on every visit. From bullets to buttons. The Batteries fascinate me especially knowing what they looked like in their prime and what they went through during the siege. If there are ghosts, then they are there. .

That’s really interesting Robert. My visit inspired me to learn more about WW2 in general, but I’m inclined to agree with you about the ghosts. Corregidor was a very moving experience for me and I’m sure many others. They have done an amazing job preserving the island too.