Makam Purba (ancient tomb) the roadside sign reads. The sign has been there for years. Since I already knew the word ‘makam’ meant tomb, I’d always assumed it was ‘just’ a graveyard. Out of respect for the dead I don’t typically sightsee in graveyards, but on a quiet errand-running day, in the middle of a pandemic-era lockdown, I did just that.

As I was passing the scenic area of Ulu Melaka, my car took a sudden swerve into nearby Masjid Jami’ul Qadim mosque’s parking lot. I was suddenly compelled to ask two roadside vendors about the sign and the ‘ancient tomb’. I think I really just wanted to talk to other humans, so asking strangers questions about something would be a good ice breaker. But their information was polite, brief and to the point. Not quite the enthusiastic response I had hoped for. They directed me to a nearby road, said it wasn’t far and that was pretty much the end of our chat. I also got the impression that neither had been there before either, or had ever given it a second thought.

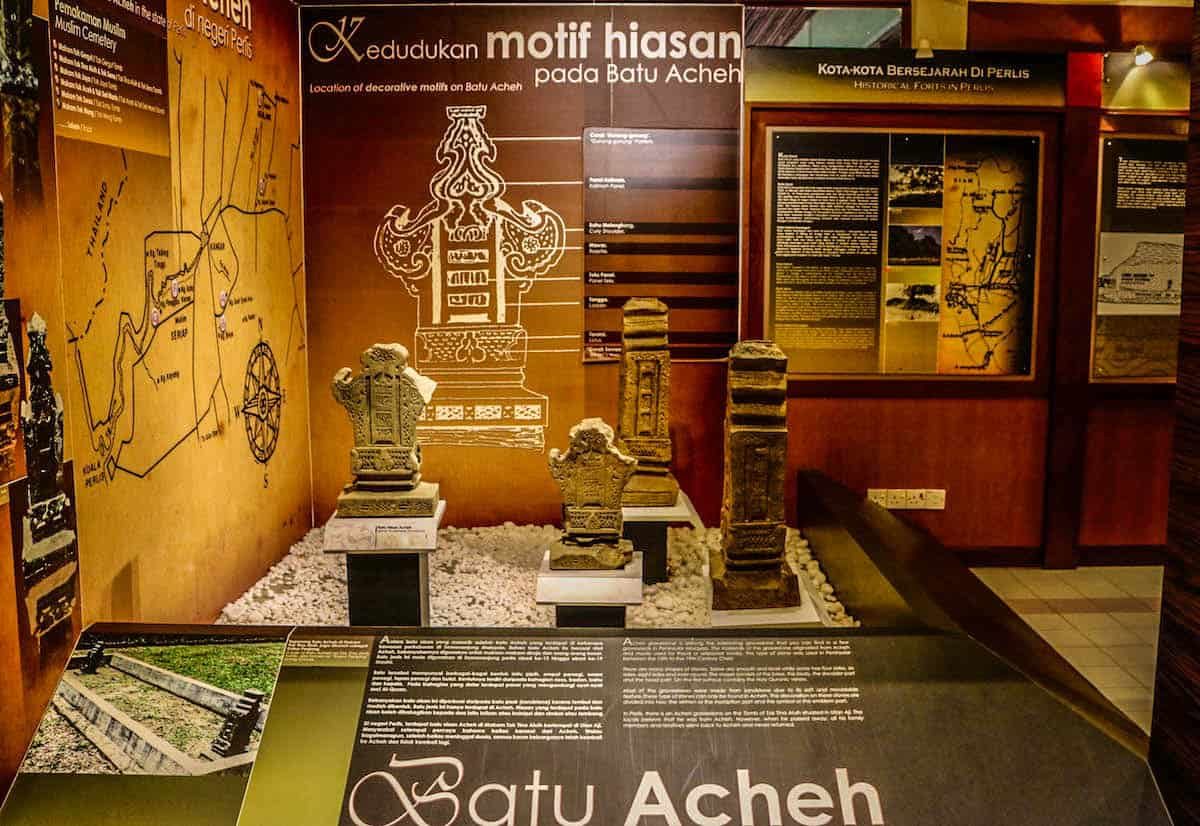

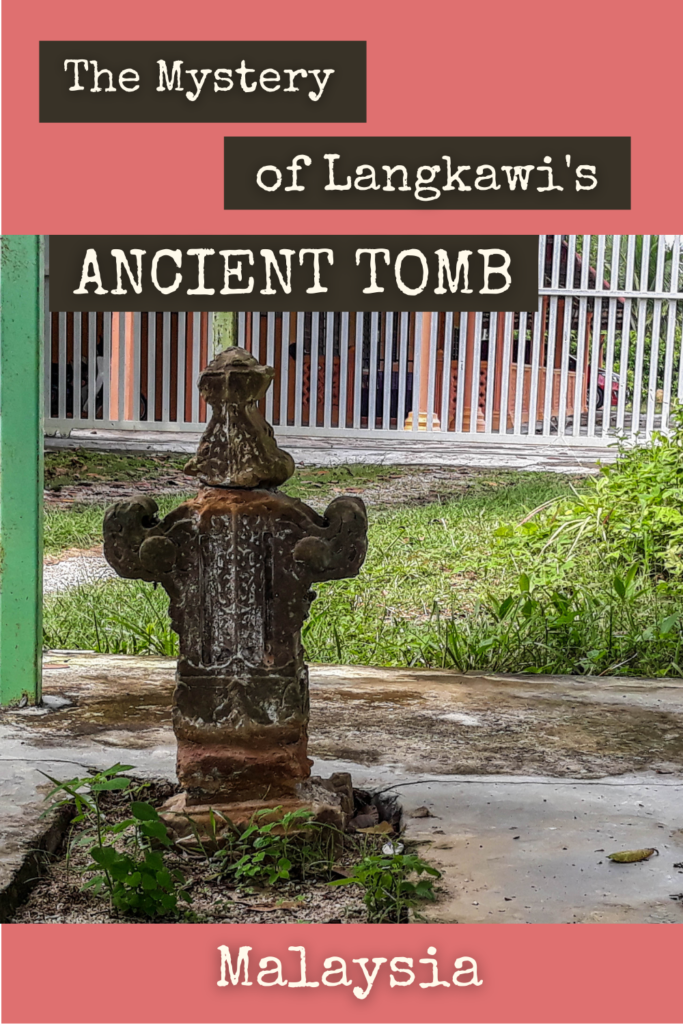

I did a U-turn out of the parking lot and headed down the small side road. It was a dead end. In fact, it was basically two households’ driveway that splintered off kampung style, into a couple of motorbike paths into the jungly yonder. But low and behold, between the two houses, below what looked like a bus stop shed were two Batu Acheh (Aceh stones). I now recognized this gravesite from random internet photos, but I’d not previously realized the significance of the grave itself. If these grave markers are authentic, then they are hundreds of years old and true relics!

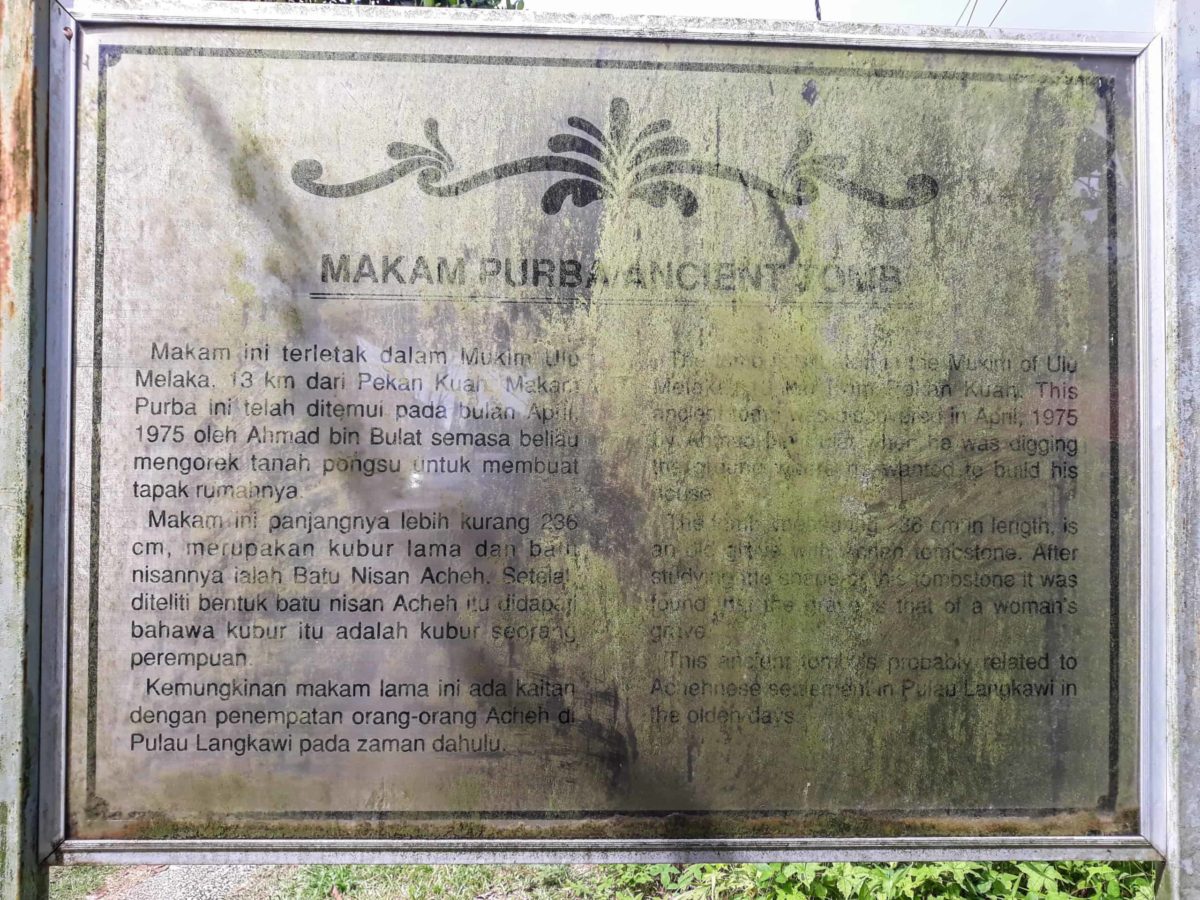

The barely readable sign (English part) reads:

‘The tomb is situated in the Mukim of Ulu Melaka, 13 km from Pekan Kuah. This ancient tomb was discovered in April 1975 by Ahmad bin Bulat when he was digging the ground where he wanted to build his house. The tomb, measuring 326cm in length, is an old grave with Acheh tombstone. After studying the shape of this tombstone, it was found that the grave is that of a woman’s grave. This ancient tomb is probably related to Achehnese settlement in Pulau Langkawi in the olden days.

I stared at the grave and felt a little embarrassed to be practically standing in these people’s yards. How many years have they endured gawking tour groups murmuring outside of their houses? I took a few photos and quietly crept away. But a week later I wanted to know more. First stop Google.

Now this is where things get interesting. And confusing. I was already familiar with Batu Acheh grave markers, but not so much with their historic significance. Thus, I entered an online rabbit hole of blog posts and research papers which required a lot of Google translate for me to comprehend even the basic gist of the various information they provided. A tedious task, by the way, but fascinating.

Batu Acheh are more than just ‘ancient tomb’ gravestones.

Batu Acheh (Acheh stones) are a gravestone/tombstone style that originated in 13th century (1200s) Banda Aceh, Indonesia and made its way to various ancient kingdoms in Malaya (and beyond). These special gravestones were reserved for sultans, high profile merchants and high-ranking individuals and their families. That in itself says a lot.

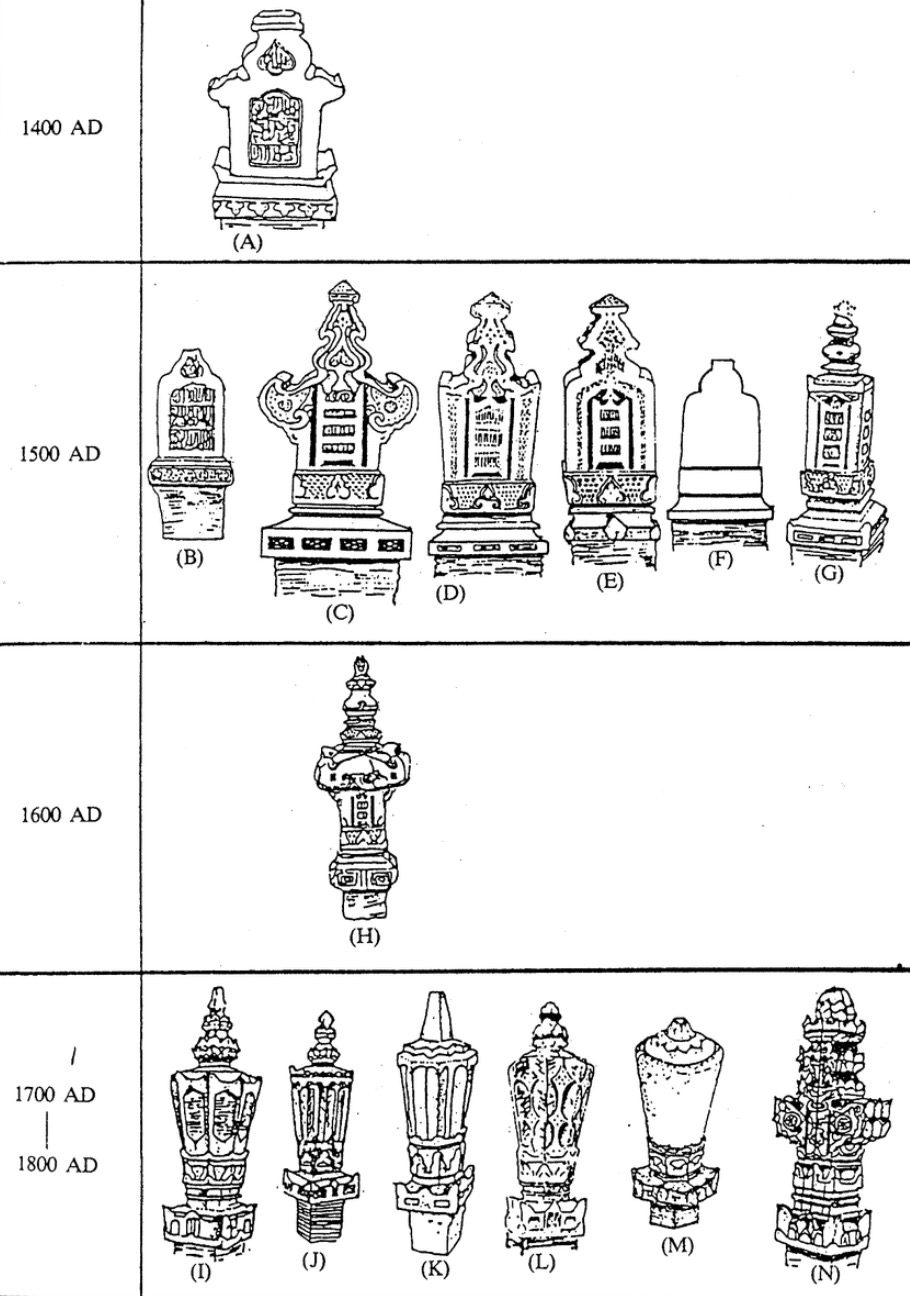

The ancient tomb in Ulu Melaka was apparently two separate grave sites (and two sets of Batu Acheh gravestones) at the time of their original discovery, in 1975, but somewhere along the line it became just one set. Archeological researchers have categorized Batu Acheh into different ‘types’ which helps indicate the stone’s age (and the deceased’s gender). The Makam Purba ancient tomb(s) are said to have been type H (H1 and H2), which is a design apparently produced in the 14th and 15th centuries (1300s and 1400s). Researchers say that the discovery of Batu Acheh in Langkawi is proof that the island played an important role as one of the administrative districts in the Kedah Malay Sultanate.

So, who was buried at Makam Purba Ancient Tomb?

That’s a big mystery. I followed a couple of leads and compared many contradicting timelines. Google translate is also not kind to Bahasa Malayu and translated sentences often become very nonsensical. Centuries can be misreported too; 13th century is the 1200s not the 1300s (or 1400s) as some seem to think. Pronouns such as he and she tend to also get mistranslated. It only takes a few of those mistakes to make one’s head spin. But it’s a fascinating research effort none the less.

One comment on a blog post, first led me to Singapore: ‘Isn’t this the tomb of Tun Jana Khatib, who was killed in Temasek (present day Singapore) but his body was found in Langkawi?’

The story (short version) is about a trader from Pasai, Sumatra. His name was Tun Jana Khatib. He was highly respected for his personality as well as charity work with locals. Apparently, there was some misunderstanding involving the destruction of a betel nut tree. This angered the King and Tun Jana Khatib was sentenced to death.

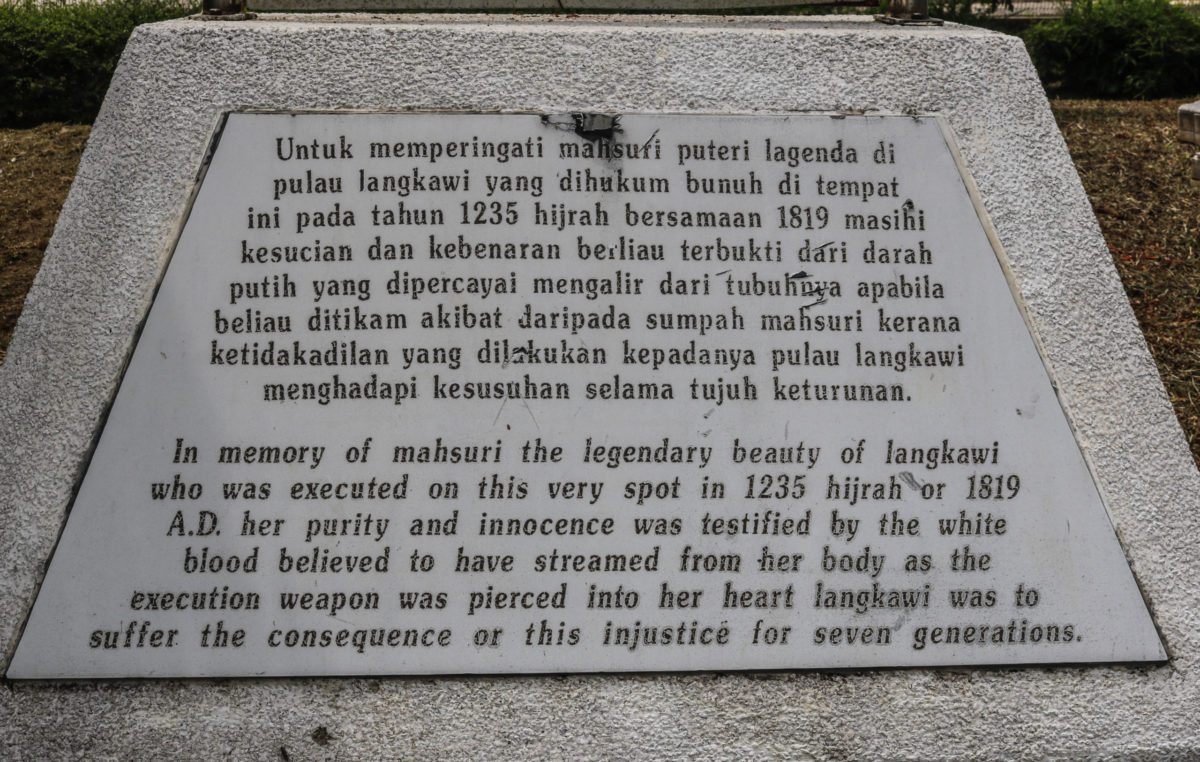

Just prior to his death, Tun Jana Khatib proclaimed, “O you all! Know you all. I relented this death! But the tyrant king will not escape just like that. He only paid the price for the tyranny. And believe me Singapore will be in chaos! There will be a terrible catastrophe!”. Sounds eerily similar to the Legend of Mahsuri, doesn’t it?

It gets better though. While they were taking Tun Jana Khatib’s body to the graveyard, he vanished into thin air. His blood stains turning to stone and a huge thunderstorm immediately hit Singapore. Needless to say, this freaked out a few people. Even more so when people in Langkawi discovered his body on the beach. There was even a poem (or clue) written about the incident, and documented by Tun Seri Lanang, in 1612. Tun Seri Lanang was one of the credited authors of the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), which was edited in 1612.

Duck eggs in Singgora,

Pandan is located skipped,

Blood drops in Singapore,

His body is abandoned in Langkawi.

-Tun Seri Lanang

Would a random washed ashore body warrant a special Batu Acheh tombstone? Maybe. Maybe even more so if the body was of a well-known individual. And since disappearing was a special talent of Tun Jana Khatib, then maybe that accounts for Ulu Melaka’s now missing second ancient tomb.

Another online research source claims the ‘ancient tomb’ is the grave site of Permaisuri Melur; the daughter of the King of Acheh. And she is credited as the ruler of Langkawi when it was the administrative center of the Kingdom of Langkasuka during the 14th century (1300s). That same source then goes on to say the tomb belongs to ‘Queen’ Derbar Raja Merong Mahawangsa, Sultan Muzaffar Shah I (the 5th Sultan of Malacca, who died in 1495; the 15th century), during the Langkasuka reign. However, Wikipedia prefers Derbar Raja Merong Mahawangsa to be a him; legendary warrior Merong Mahawangsa; the first King of Langkasuka. Langkasuka also being referred to as ‘modern day Kedah’.

Another version of that story is that the ancient tomb is from the time of the war with Siam (now Thailand), which began in 1821 (the 19th century). According to the myth/ rumor, there was also gold stored in the ground of the nearby mosque; present day Masjid Jami’ul Qadim, in Ulu Melaka. A mosque was apparently originally built at that location during the Merong Mahawangsa’s days and was the first mosque built in Langkawi. Confusing? You bet!

Langkasuka, by the way, was a kingdom established in the 2nd century and dissolved in the 15th century (1400s). Its exact location seems to still be under some debate, but the majority tend to sway closer to the Pattani, Thailand and the Southeast Thailand area. Not Kedah.

And despite many references to Langkawi having been named from the word ‘Langkasuka’, historic documents report that Songkhla, Thailand was the center of power for the northern most territories of the Malay Kingdom of Langkasuka from the 3rd to 13th centuries. So why on earth would Langkawi be an administrative center?

Hmmm…But the Malacca (Melaka) connection makes sense. Ulu Melaka. The kampung where the ancient tomb is located. The Straits of Malacca also run from Melaka past Langkawi. Ulu means ‘head’. Head could be referring to a direction or perhaps a reference to an administrative position?

And who’s to say what the actual land masses looked like hundreds of years ago? Surely the earth has shifted in a few places over the years. I once heard that Bomohs from Kedah mainland used to row their boats out to Langkawi waters to release bad juju spirits. Today that would be a triathlete endeavor, but back in the olden days maybe land masses were closer together?

If you’re already confused, you’re not alone. I went round and round chasing these dead folks and still came up empty handed. To make matters even more intriguing, in 2015, archeology teams from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia found three more grave sites in Langkawi with Batu Acheh grave markers. One in the Ulu Melaka area and two more in Kampung Kubang Badak. Thus, the mystery continues. Who were these people and what are their stories?

If you’re interested to try to solve the mystery yourself, start with a visit to Makam Purba ancient tomb and see the Batu Acheh first hand. They might lead you down an internet rabbit hole or they might just lead you to the truth.

Makam Purba Ancient Tomb

Ulu Melaka, Langkawi (look for the sign near the Jami’ul Qadim Mosque)

*The site is very close to people’s homes, larger groups may find it less intrusive to simply walk back from the main road

For more unique sightseeing options in Langkawi, check out: 15 Free Things to Do in Langkawi

Land masses haven’t changed significantly over the last 500 – 600 years. Yes, continental drift, but that takes place so slowly that even if Langkawi and the mainland were on separate pieces it would only amount to a meter or so difference.

In those days to get from one to the other you rowed or sailed, and were prepared to take a whole day to do so.

I can’t even imagine rowing that distance, but I guess if the tides were favorable maybe not so labor intensive. Any guesses on the tombs’ occupants?

Try watching the Movie “Singapura Dilanggar Todak. The movie is related to Tun Jana Khatib’s spell on Singapore Island.The movie was taken in 1960’s so its black and white movie.

Thank you! I’ll see if I can find it.